The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine has been awarded to three scientists whose discoveries reshaped our understanding of the immune system, revealing how it attacks infections without turning against the body itself.

The prize went to Japan’s Shimon Sakaguchi and U.S. researchers Mary Brunkow and Fred Ramsdell, whose work uncovered what are now known as regulatory T-cells, the immune system’s “security guards.” These specialized cells patrol the body, disarming rogue immune cells that might otherwise attack healthy tissue.

“Their discoveries have been decisive for our understanding of how the immune system functions and why we do not all develop serious autoimmune diseases,” said Olle Kämpe, chair of the Nobel Committee, in a statement announcing the award.

The trio will share a prize fund of 11 million Swedish kronor (about £870,000).

A New Chapter in Immune Science

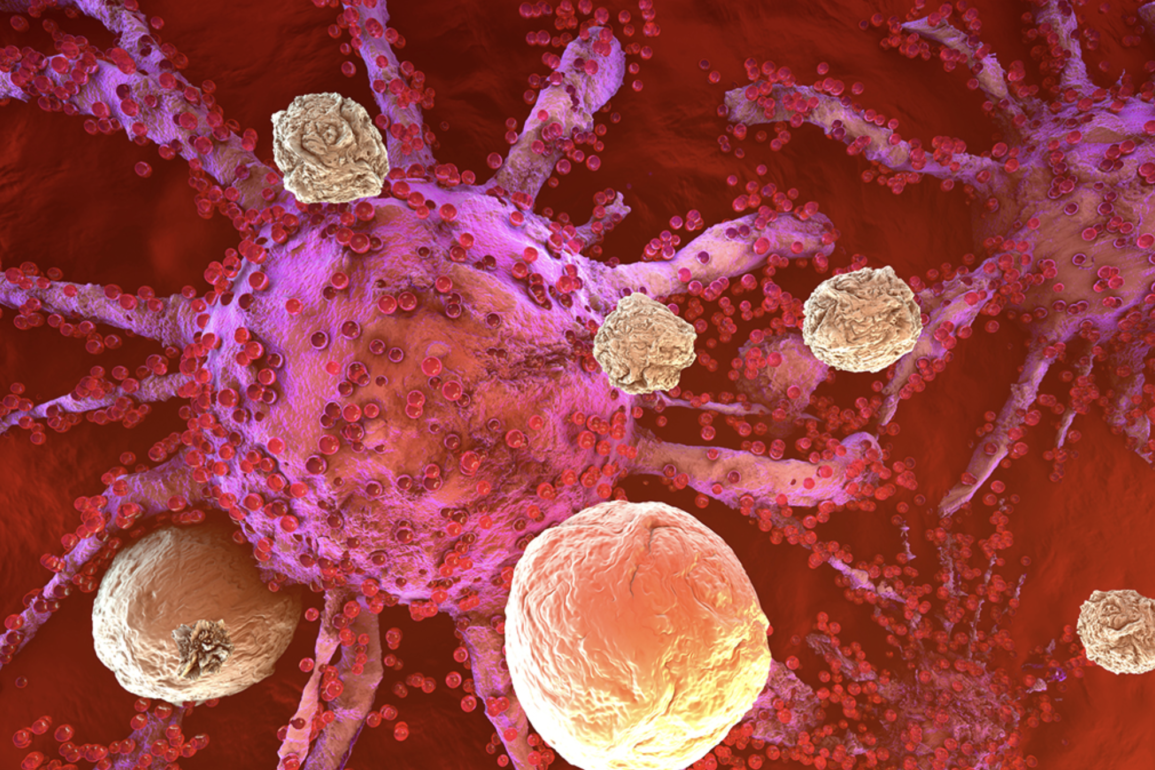

The immune system is a paradox of precision: it must mount attacks against thousands of foreign invaders — viruses, bacteria, and parasites — yet somehow spare the body’s own cells. This balancing act is orchestrated by white blood cells that carry randomly generated receptors, a process that produces an extraordinary diversity of defenses. But that randomness can also produce dangerous cells that mistake “self” for “enemy.”

Scientists had long known that the thymus, a small organ where immune cells mature, plays a key role in destroying these self-reactive cells. What Sakaguchi and his collaborators discovered was the second line of defense: a mobile corps of regulatory T-cells that police the body, suppressing immune responses that threaten to go rogue.

The Nobel panel called the discovery “foundational,” adding that it “has laid the groundwork for a new field of research and spurred the development of new treatments, for example for cancer and autoimmune diseases.”

When regulatory T-cells fail, the immune system can turn on itself, leading to diseases such as type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, or rheumatoid arthritis. Conversely, when they become too active, they can protect cancer cells from being attacked.

In cancer research, scientists are now exploring ways to reduce regulatory T-cells so the immune system can recognize and destroy tumors. For autoimmune diseases, the opposite strategy is being tested, boosting regulatory T-cells to calm destructive inflammation. The same principle could one day help prevent organ transplant rejection.

The Pioneers

At Osaka University in Japan, Prof. Shimon Sakaguchi made a breakthrough while studying mice whose thymus glands had been removed, causing them to develop autoimmune disease. Injecting immune cells from healthy mice prevented the illness — clear evidence of an internal system designed to prevent self-destruction.

Meanwhile, Mary Brunkow, from the Institute for Systems Biology in Seattle, and Fred Ramsdell, now at Sonoma Biotherapeutics in San Francisco, were studying inherited autoimmune disorders in mice and humans. Their research led to the discovery of a crucial gene governing how regulatory T-cells function.

Professor Annette Dolphin, president of the UK’s Physiological Society, called the findings transformative. “Their pioneering work has revealed how the immune system is kept in check by regulatory T cells, preventing it from mistakenly attacking the body’s own tissues,” she said. “This work is a striking example of how fundamental physiological research can have far-reaching implications for human health.”

More than two decades after their discoveries, Sakaguchi, Brunkow, and Ramsdell’s work continues to ripple through laboratories and clinics worldwide, a testament to how understanding the body’s own defenses can open doors to healing it.